- Home

- Maggie Tokuda-Hall

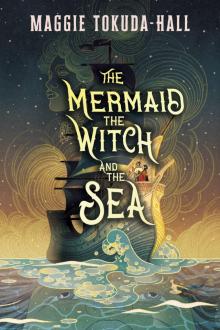

The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea

The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea Read online

Prologue

Part One: The Mermaid

Chapter 1: Evelyn

Chapter 2: Flora

Chapter 3: Evelyn

Chapter 4: Flora

Chapter 5: Evelyn

Chapter 6: Flora

Chapter 7: Evelyn

Chapter 8: Flora

Chapter 9: Evelyn

Chapter 10: Flora

Interlude: The Sea

Chapter 11: Evelyn

Chapter 12: Flora

Chapter 13: Evelyn

Chapter 14: Flora

Chapter 15: Evelyn

Chapter 16: Flora

Chapter 17: Evelyn

Chapter 18: Flora

Chapter 19: Evelyn

Interlude: The Sea

Part Two: The Witch

Chapter 20: Flora

Chapter 21: Evelyn

Chapter 22: Rake

Chapter 23: Flora

Chapter 24: Evelyn

Chapter 25: Rake

Chapter 26: Flora

Chapter 27: Evelyn

Chapter 28: Rake

Chapter 29: Flora

Chapter 30: Evelyn

Chapter 31: Rake

Chapter 32: Flora

Chapter 33: Evelyn

Chapter 34: Rake

Chapter 35: Flora

Chapter 36: Evelyn

Chapter 37: Rake

Chapter 38: Flora

Chapter 39: Evelyn

Chapter 40: Flora

Chapter 41: Evelyn

Chapter 42: Flora

Interlude: The Sea

Part Three: The Sea

Chapter 43: Evelyn

Chapter 44: Genevieve

Chapter 45: Rake

Chapter 46: Flora

Chapter 47: Genevieve

Chapter 48: Rake

Chapter 49: Evelyn

Chapter 50: Genevieve

Interlude: The Sea

Chapter 51: Flora

Chapter 52: Rake

Interlude: The Sea

Chapter 53: Flora

Chapter 54: Evelyn

Epilogue: Genevieve

Acknowledgments

Long after the sun had set, when the passengers were nestled neatly in their cabins, the crew gathered on the deck of the Dove. They’d been at sea for a fortnight, playing the role of any passenger vessel crew — all “yes, sirs” and “no, miladys” — seeing to the needs of the stiff-legged landsmen with exaggerated obsequiousness. But no more.

Rake stood at the helm, just below the Nameless Captain, as was his place. The ragged crew below them were the captain’s men, chosen for their savagery, their drunkenness, and their predilection for thievery and murder. But it was Rake they answered to at sea.

“It’s time,” Rake said, and the men scattered belowdecks.

Sleep-fogged passengers were pulled roughly from their bunks and dragged, questioning and sputtering, to the foredeck. The captain scoffed; even their nightwear was finery, silks with careful stitching.

As was ritual, the strongest man was pulled from the ranks of the passengers and forced to his knees. On this particular voyage, he was a spice merchant named Mr. Lam, headed to the Floating Islands without his wife and his children to see about the famous marketplace there. He could be no more than twenty-five.

“Come on, then, Florian,” Rake said. “Time to earn your britches.”

It had been Rake’s idea: The name change. The men’s clothes. Being a slip of a girl may have been tenable in Crandon, but it wasn’t here on the Dove. Not among these men. In taking this man’s life, Flora could start a new one. Her life as Florian.

The cost was simple. Rake slipped Florian a dagger.

“Show them,” Rake whispered. Not just the passengers, as was Florian’s official charge, but the other sailors aboard the Dove. They needed to see who this child was, the man this girl had become. Rake could tell from the solemn nod Florian gave that he understood Rake’s words exactly.

The child stepped forward, and though he was small-boned and skinny from strict rations, the passengers fell silent. The long, silver dagger in Florian’s hand shone like the moon in an otherwise black night.

The Nameless Captain cleared his throat, all theater and cruelty. “It gives me no great pleasure to announce to you fine people that the Dove is no passenger vessel. She is a slaver. And all of you aboard are now her chattel.”

Sobs and cries of dissent rippled through the passengers. One foolish old man even cursed at the captain. A blow from Rake across the man’s chin crumpled his aged and spindly legs for him, and he hit the deck with a crash of bone on wood. The scuffle only caused more shouting and wailing until the captain raised his pistol into the air and fired once.

Silence returned, save for the sound of the sea lapping against the Dove.

“If any of you are thinking of mutiny, I can promise you” — he motioned to Florian, who slipped behind the trembling Mr. Lam, dagger poised —“we don’t take kindly to mutineers.”

Though the man begged for clemency at a whisper, Florian dragged the dagger across his throat. Lam’s blood spilled down the front of his nightshirt, and his thick, muscled body fell to the deck. Two of the crewmen hauled the dying man up by the armpits and held him for passengers to witness how the last shudders of life left him. Florian wiped the blood from the blade on his sleeve.

With the passengers now sufficiently terrified, the captain had them locked into the slave quarters, in the hold of the ship. The Dove’s spacious cabins would be used henceforth by the crew, who until then had been taking turns in the hammocks strung up in the stores.

Belowdecks, the passengers wept.

Abovedeck, the crew chanted, “Florian, Florian, Florian, Florian!”

He was a captain’s man now — Rake had seen to that. As safe as he could be among his peers. The child had competently changed stories more than once, and swiftly, too. Rake had seen it happen. What was one more seismic shift? From child to adult. Innocent to murderer. Girl to man.

And Florian, who still had Mr. Lam’s blood on his sleeve, smiled into the darkness.

Evelyn washed her hands again. The telltale sand under her fingernails stubbornly resisted the fine soap from Quark that her mother, the Lady Hasegawa, had imported especially for her. Her mother claimed that only a foreign soap meant for rice-paddy farmers could possibly conquer Evelyn’s dirty fingernails, since her habits were far too coarse for a good Imperial girl.

It was a rude thing to have said, but more so because the Lady said it in front of her lady’s maid, who was from Quark.

And sure, maybe digging about the shore near their home looking for shells was not a most ladylike activity. The whole coastline was black from the filth of the Crandon port. Crandon was the capital of the Nipran Empire, and nearly every type of trading vessel passed through her waters. But it was not so dirty that lovely pink and white shells could not be excavated by those with the patience to do it.

Evelyn had convinced her own lady’s maid, Keiko, that the Lady Hasegawa would never again find out that she’d been scrounging on the shore. But now Evelyn was carelessly close to breaking that promise, which could lose Keiko her job, not to mention any reference the Lady Hasegawa might give her. But still. Somehow Evelyn could not be called away from her messy hobby. It was as though the sea called to her especially.

“Miss, the Lady has called for you again,” Keiko said. She was a little frantic now. As Evelyn’s maid, she’d been subjected to all manner of admonishment for Evelyn’s many irresponsibilities, but mainly her tardiness. This afternoon’s tea would be no exception.

“I’m sorry, Keiko. Truly. But look at this one!”

Evelyn held up a whelk shell. A spiral of blue worked its way from tip to door, and only the very point of its apex had been snapped off. “It’s practically intact!”

“Hold still.” Keiko grabbed Evelyn’s hands and, finger by finger, dragged the blunt end of a sewing needle beneath the nail, scraping out the grit. It hurt, and one of her fingers bled, but Evelyn was glad for Keiko’s help. She always was.

“Thank goodness for you, Keiko,” Evelyn whispered, “or my mother would’ve disowned me years ago.”

Keiko smiled, gave Evelyn a nudge with her shoulder. “Thanks to the Emperor, you mean. Now go, please. Before I’m sacked and you’re cut out of the family.”

Evelyn gave Keiko a quick kiss on the cheek and ran to the sukiya, where her mother’s tea ceremony was held every day.

The Lady Hasegawa and Evelyn had been staying in their Crandon home since Lord Hasegawa had been forced to take a consultancy role in the family’s shipping company. The Hasegawas had come upon hard times in recent years, and though the Lady Hasegawa would never admit it, they had all but abandoned their country manor and nearly all of their staff. And though they were still attended to by a handful of footmen, ladies’ maids, guards, a cook, and a gardener, one could scarcely ignore the conspicuous lack of service in their household. Hasegawa was an old name, and it was her father’s dishonor that they were not better kept.

So many servants gone meant that Evelyn had hardly any family left, either. The servants had been the ones who had raised her, after all. It had been her nanny who’d kissed her skinned knees, the stable boys who’d played chase. She barely knew her parents, and they certainly did not know her.

However, without fail, the Lady Hasegawa still demanded the high tea ceremony each afternoon, and Evelyn’s presence was mandatory. Evelyn wasn’t exactly sure why. While she liked a good rice ball as much as anyone, tea was invariably boring and painfully tedious, especially in the summer, when there was so much to see and do.

All of which existed outside her mother’s sukiya.

“Evelyn, you are late,” the Lady Hasegawa said by way of salutation. “Again.”

“My apologies.” Evelyn bowed low, trying her best to look properly conciliatory. Then she took her seat, accidentally nudging the table with her knees. The preponderance of small dishes clattered.

A quick exhalation through the Lady Hasegawa’s flared nostrils was all Evelyn needed to be reminded of her mother’s perpetual disappointment in her. How wearying it must be, Evelyn thought, to bear the burden of such ceaseless inadequacy. Still, at least she knew her mother, could recognize the moods — mostly displeasure — that flitted across her face. Her father was as unfathomable to her as the bottom of the sea, and nearly as distant. Once she had asked him if he loved her or not. In response he had drained his drink wordlessly and left the room.

The Lady Hasegawa motioned for the tea to be poured, which was done in silence. Evelyn did her best to handle her teacup with grace. She’d broken two already and been banned straight out from using the heirloom porcelain, a humiliating rule enforced even in company.

“As has likely become clear — even to you — our family has come upon some hard times,” the Lady Hasegawa said.

Evelyn nearly dropped her cup. Her mother never admitted to the financial woes of the Hasegawas, even though they were glaringly obvious. How strange it was to hear their truth so plainly stated. For once.

“Yes, Mother.”

“As such, Lord Hasegawa has decided it’s time for you to wed. You’re nearly sixteen years old. And, thanks to the Emperor, your father has found you a suitable match. One who does not demand too much in the way of dowry.”

Evelyn put down her cup gracelessly. Hot tea sloshed over the lip of the cup onto her hand. It burned until it was cold. Evelyn made no effort to brush it away, instead focusing on the gift of distraction it gave her in this terrible moment.

“You should be glad to know,” the Lady Hasegawa said loudly — loud enough so that the few servants they still had left in their employ could hear her — “that your father has done quite well for you, despite your many faults, thanks to his high connections within the Emperor’s ranks. Your husband may be new money — garnered in the silk trade — but he’s achieved something for himself and even served in the Imperial Guard. I hear he was most gallant in the service. He’s made quite a name for himself. All of which, let’s be frank, is substantially better than I ever dreamed for you.” She took a sip of her tea. Her manners were perfect, of course, her hands cupped delicately around her cup just so. “You shall be joining him at his residence.”

“Is he . . . is he here?”

“My goodness, no,” the Lady Hasegawa said brusquely. She deftly picked up a piece of squash in her chopsticks and elegantly deposited it in her mouth. She chewed thoughtfully, as if imagining the relaxing, daughter-free future this arrangement promised. She was smiling, Evelyn realized. Triumphant. “No, he’s in the Floating Islands.”

The Emperor had many armies and navies, consulates and ambassadors, all over the Known World. Nearly all of that world was colonized by the Nipranites now, though some colonies were younger, still rough around their edges. Iwei was, of course, the oldest colony. If only she could be sent there! It might be the smallest of the many island nations that made up the Known World, but it boasted famously temperate weather, and all the best wines were imported from there. Even Quark would have been better. It was a new colony, certainly, but it was so close to Crandon, only two weeks’ sail on a clinker. Culturally different. Life was a little cheaper there, which lent it a frightening air. But if she were in Quark, she could still come home now and again.

The reach of the Imperial Guard stretched far beyond casual travel, however, and the Floating Islands were proof of this. They were a several-months-long voyage, and an expensive one. With so many days on the open sea, it was risky enough not to be taken casually. If she went to the Floating Islands, Evelyn realized, she’d likely never come home.

“Yes,” the Lady Hasegawa said dreamily. “Your father has done quite well.”

Like all the children of Crandon, Evelyn had been reared on the tales of the savagery and magic of the Floating Islands. It was said they housed the Known World’s last witches. Actual practical witches. It was only thanks to the Emperor that witches were finally all but extinct, and the world was safer for it. And while Crandon, as the capital of the Nipran Empire, was cold and orderly, the Floating Islands were notoriously a nation of vagabonds, baleful merchants, and danger. But then, that was what Imperials said about basically all of the colonies. The ruling classes imported the colonies’ goods and prayed that the people who supplied them would stay upon their native shores.

A shiver raked down Evelyn’s spine as she tried to imagine herself riding the infamously dangerous wood-and-rope elevators that rose from the Islands’ craggy cliffs.

If one thing was for certain, it was that Evelyn’s parents had finally found the most expedient and honorable way to be rid of her. What a small cost her dowry must have seemed to them.

She would leave with her belongings packed into her casket, as so many Imperial girls had done before. It was a tradition born of the most calculating kind of practicality, serving the dual purpose of showing the husband that the girl would be truly with him until death did they part, while also providing, at her family’s expense, a means for her burial. It was macabre, and Evelyn’s skin crawled, thinking of her kimonos and her corsets crammed into the vessel that would one day house her corpse. She had often thought of casket girls with pity — that their parents would be so crass, that their lives would be so transparently close to death, that their futures would be so bindingly arranged.

And now she was one of them.

Evelyn was to depart for the Floating Islands within a fortnight. Without the expense of housing and keeping a daughter, the Lady Hasegawa would be taking on two new kitchen girls and an additional valet. Though it was customary for a lady’s maid to

accompany her lady, Keiko would not be going with Evelyn. Instead, Keiko had been offered either a demotion to the laundry or a letter of reference.

It was a cruel thing the Hasegawas were doing to Keiko, and it infuriated Evelyn as much as did her own fate. For Keiko’s part, she’d held herself together admirably under the circumstances. She padded into the room, her footfalls nearly silent on the tatami mats, in the way that most practiced servants’ were.

Keiko was, Evelyn reflected, too good for the Hasegawas. She resolved that she would tell her so before she left.

“Are they asleep?” Evelyn asked.

“Lord Hasegawa has taken his wine for the evening.” Keiko hardly met Evelyn’s eyes. Instead, she persistently averted her gaze to an imperfectly tied curtain or a speck on the vanity mirror that needed polishing. Keiko had been Evelyn’s personal maid since they were both children, and her best friend for nearly as long. Evelyn knew Keiko’s face as well as her own; tonight it was wrought with despair.

“Come on.” Evelyn pulled the blankets aside, making enough room so that Keiko could lie beside her. Keiko sniffled but obeyed, finding her place in Evelyn’s arms.

Evelyn stroked Keiko’s hair, which was soft and familiar to the touch, the dark and lovely brown of good soil. Keiko was not Nipranite, though she bore a Nipranite name. Most servants did. The Cold World name her mother had given her had been long and complicated, too much for the Imperial tongue. Evelyn could not remember it. She could remember every freckle on her face, though.

She lifted Keiko’s chin with her finger, tipping the girl’s face toward hers. Keiko’s freckles blurred beneath the tears that converged at her sharp chin. Evelyn stopped to consider Keiko’s lips before she kissed her.

Keiko’s kisses tasted of salt. Like the sea. It was odd, so unlike Keiko. It was equally unsettling and lovely. With each kiss Evelyn felt further from her new life as a casket girl and closer to Keiko. Closer to home.

But even as she tried to lose herself in the softness of Keiko, of her mouth and her legs and her neck and her cheek, Evelyn couldn’t help but wonder if her parents’ choice to deprive her of her most beloved lady’s maid was not just frugal but calculated.

The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea

The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea