- Home

- Maggie Tokuda-Hall

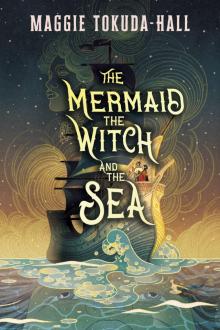

The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea Page 12

The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea Read online

Page 12

“Please. Florian needs your help.” She paused as the woman looked at Florian appraisingly. “I’m Evelyn,” she added, rather stupidly. The woman had not asked.

“Been expecting you,” the woman replied. “I’ll take that bracelet, Evelyn,” she said curtly. Evelyn had not realized she’d shown it. Hastily, she undid the clasp and handed it to the woman. She took it without looking at it and stuffed it in her cleavage.

“Can you help him?”

“What. This child?” She lifted Florian’s arm and then dropped it unceremoniously. “That was a better question for before you handed over your jewelry.”

“They said you were a healer?”

“They say I am a witch,” the woman corrected. Evelyn did not reply. Apparently the success of their eradication had been exaggerated. Perhaps, Evelyn hoped, the tales of their untrustworthiness had been, too.

“And yes,” the woman said, “I can help this person you’ve put on my kitchen table, and I can do it before dinner.”

She rolled her head in a circle, stretching her neck, and sighed. In the strange and wavering light of the candelabra, she was not beautiful. But she fit. The cruel cut of her lips and the sharpness of her eyes. Her traits seemed perfectly suited for her kitchen, seemed so appropriate within it. In the darkness, surrounded by seemingly innumerable potted herbs that cast ghostly shadows upon the walls. A woodstove piped warmth in, and finally Evelyn could feel her muscles unclench, just a little, in the comfort it offered.

“You can call me Xenobia.” It was an odd way to phrase it. Was that not her name?

“My name is Evelyn Hasegawa and —”

“I don’t care who you are,” the witch interrupted. “There are a thousand girls just like you in this world, and I haven’t the patience, fortitude, or, frankly, the time left in my life to know you each.”

Evelyn felt her mouth go slack. It was like the witch had punched her. “I — I paid you —”

“Yes, indeed. And I’ll help your friend here. But you.” She eyed Evelyn up and then down, her lips pursed into a thin, cruel line. “You must go. Your friend and I have much work to do, and from the stories the wind tells me, it sounds as though we have precious little time to do it.”

“Florian?”

“Is that what you call this person? Yes, then. Florian.”

“What makes you think you have anything to do with him?”

Xenobia rolled her eyes. “Because I am older than you and wiser. And because I do magic and I know things. That’s what I do. What you do is sit around and brush your hair and read romance novels, if I have you pegged right.”

Evelyn’s eyebrows rose, completely of their own affronted accord. “You’re just a crazy old lady. And a rude one at that.” She looked about the kitchen for any obvious signs of madness. “And I’m not leaving, not until you help Florian.”

“Fine.”

Xenobia examined Florian’s wound once more and, to Evelyn’s absolute horror, stuck her finger in it. She rubbed the blood her finger came away with between her forefinger and thumb thoughtfully and then spat in the wound. Blessedly, Florian was still unconscious and did not feel the pain or the disgust this would have certainly caused. But before Evelyn could yell out in protest — which she fully intended to do — the witch slammed her elbow into a small, wood-framed looking glass that hung on the wall behind her. It shattered immediately, and one long shard fell to the ground.

Evelyn made a noise of exclamation that was more shout than words, but Xenobia waved her hand dismissively.

“Your friend is not whole,” she said, as though that explained anything. “And until I can teach this Florian to be whole, nothing will be accomplished and destiny will be delayed.”

“Destiny?” Evelyn asked, but the witch either did not hear her or simply ignored her. Evelyn imagined it was likely the latter.

With some effort, the witch reached down to the floor and picked up the long shard from the looking glass. She held it in her fists over Florian’s wound and began to murmur words Evelyn could not hear.

The evidence of Xenobia’s madness, it seemed, was unfolding before her eyes.

Florian was dying. She had no time to fuddle about with charlatans who believed in magic. She was just taking a deep breath so that she might impart her fury on the so-called witch when Xenobia looked up.

Her eyes were foggy with what looked like storm clouds that had not, just moments ago, been there.

She smiled.

Evelyn stepped toward the table where Florian lay and saw why.

His wound was healed. All that remained of what had been bleeding was a small brown pucker of skin. Like a scar, but from years and years ago, a scar whose origin was all but forgotten.

Xenobia put the shard down on the table next to Florian and pointed with one long finger toward the door. “I have proved myself. Now you must do the same. Go, and do not return for a month. I need all that time and more with Florian here, if I should serve my purpose well in this world.”

“But —” Evelyn interjected. She did not speak the language of the Floating Islands. She did not have anywhere to go. And she’d just given away her only belonging of any value. Her eyes filled with tears. “I’m not leaving without Florian.”

Xenobia’s lips pursed once more, and she looked at Evelyn dubiously. “Evelyn Hasegawa, you say. Is that Lady Hasegawa?” Evelyn nodded, hopeful that her rank might help in this moment of dire need. Finally, Xenobia smiled a strange crooked smile. “If you can make yourself useful, you may stay.”

Evelyn nearly passed out from relief. “Of course.” She had no idea how to be of any use in any home, let alone the home of a witch. She’d never washed a dish or cleaned a floor or cooked a meal in her life. Her few attempts to help Keiko over the years had varied from annoying to disastrous. Xenobia didn’t need to know that. This was a fresh start. She would do her best.

For Florian.

The Imperial girl had been an unforeseen complication.

Just the thought of it — an Imperial who served the Sea? — made Rake’s mind twist into strange, indecipherable shapes. It just couldn’t be. The Emperor sought to own the Sea, just as he owned nearly all of the Known World. Just as he now owned Quark. And yet, here was this girl, this stupid girl, who’d somehow improbably — impossibly! — solved a mystery that had bedeviled sailors for centuries.

Had it been anyone else in the crew to point this out to Rake, he would never have believed it. But Flora. If you had told Rake years ago, when he’d first met that feral little girl, that he would come to care for her, he would have laughed. But now that little girl had grown into a fine man. An excellent sailor. He deserved better than life aboard the Dove. He deserved better than to serve the captain. Someday, Rake believed, Florian would serve the Pirate Supreme, too.

As Rake had done. As Rake still did.

Rake had never served the Nameless Captain, not truly. His orders came from the Pirate Supreme, and those orders had been clear: Infiltrate the crew of the Dove. Direct the derelict captain to the arms of the Pirate Supreme so that he might stand trial. Justice waited. Justice had waited for years.

But now, the girl and her blood. The mermaid.

He sent a message to the Supreme and awaited command.

Not a night later, an albatross flew over the deck of the Dove.

It was the dead of night, so Rake knew it was not some lost bird. It was a messenger.

It landed on the gunwale and waited patiently for Rake. The note was tied to the bird’s spindly leg, and as soon as Rake freed it, the bird took flight.

The two souls and the mermaid must be saved, the note said. But all other crewmen must pay their fair price to the Sea.

The note did not mention the brother, or any clemency he could expect. Rake nodded. Fair was fair. And if the Pirate Supreme was expected do the Sea’s bidding, well, then blood would have to be paid.

So it was. So it had always been.

I will come with the

Leviathan. This time, we will have him.

The Pirate Supreme. The regent of the Sea would be there, in person, to see the Nameless Captain caught. In their best and biggest ship. Something like pride lifted its head in Rake’s heart.

Florian would escape. The mermaid would be returned.

The Nameless Captain would know justice. Finally.

Rake crumpled the note and dropped it overboard. The wind carried it back and away until it was invisible in the night.

Silently, he stepped to the mast, where he could see Florian and the Imperial girl already bent on escape. Rake tried not to smile.

Any word to Alfie’s protection had been a lie. Rake had known it. He’d known it when he’d said it, and he knew it now as he watched Fawkes lash him at the captain’s command. Alfie’s narrow hands were strapped to the mizzenmast, and though he had taken the first strike without noise, by the third he howled with piteous pain.

Fawkes relished his work. Rake could see it in the ugly glint in his eye. He’d rolled up his sleeves, revealing his thick forearms to the sun. As if Fawkes hadn’t already punished the boy enough. As if his cruelty didn’t already scar the boy. Between lashes he cracked wise with the men, who laughed and ignored Alfie’s cries. Rake did not. Could not. Despite himself, despite his awareness of the boy’s near uselessness, a prickle of guilt rankled him. Would Florian have left if he knew this fate awaited his brother?

The captain had not even stayed abovedeck to watch. Bored, maybe. Indifferent to the pain he caused. The passengers, now prisoners, watched in horror. One of the ladies wept openly, a strangely incongruous sound amid the open laughter of the men.

Somehow, the Lady Ayer and her maid were among the missing, presumed by the captain and crew to have escaped with Florian and the Lady Hasegawa. It was a sensible thing to assume. The Dove was not an enormous ship, not like an Imperial galleon, but she had her nooks and crannies. She was a proper passenger vessel, after all. They were hiding somewhere. Rake didn’t know where, nor did he have time to find them. They were on their own. Just like poor Alfie.

The whip cracked against his back with a wet smack. Alfie’s body had gone limp, hanging by his hands. He’d passed out. That was good, Rake thought. Better to receive the rest of his whipping from the vantage point of unconsciousness. His back was a bloody mess, and his pants were filthy with the evidence of his pain. Blood and piss. The life of a pirate.

If they had known, if they had truly understood, would Alfie and Flora have come aboard the Dove? They were only children in search of a bed. In search of food. Though Rake had known, and yet here he was. What would his life be had he not been cruel in his youth? Where would he be today had he not willingly sought criminality and mermaid’s blood? His debt was a great one to the Pirate Supreme. Without the Supreme’s mercy, his bones would likely still be hanging, picked clean by gulls, off the ramparts of the Supreme’s stronghold.

“That’ll do, Fawkes,” he boomed. It had been fifty lashes. That was all the captain had demanded.

Fawkes flashed an ugly look at Rake just shy of insubordination. But he stopped.

A couple of the men helped take the boy down and carried him off to Cook for bandages. He’d be lucky if the wounds didn’t get infected. Cook would treat them with boiling water, meaning the boy was in for a second round of nauseating pain. All this before his short life was over.

For the captain had not believed Alfie when he’d claimed, truthfully, to have had no idea about the escape.

“You helped them,” the captain had hissed. And Alfie had protested and cried and wept, but it was to no avail.

He would be the one killed, Rake knew. The captain had not yet ordered it, but Rake knew, the same way he knew the wind would pick up in the afternoon.

The noose had already been around Rake’s neck when he’d seen the Pirate Supreme for the first time. It was not the Supreme’s role to attend trials. This everyone knew. So why the Supreme was there for the executions was a mystery.

Yet there the Pirate Supreme was.

The Pirate Supreme had the lean build of a knife fighter, and the scars of one, too. They were from Tustwe, likely, judging from their black skin and their accent, which was round and rhythmic. The Supreme was not dressed as Rake might have guessed a Supreme would dress. No finery. No useless frippery. Just the clothes of a sailor, albeit free of stains, and innumerable thin dreadlocks, neatly pulled back with a thin rope. They were not a man, nor were they a woman, but rather something else entirely.

Rake was of a crew that had been captured just beyond the Red Shore. They were headed to land, to drink their mermaid’s blood, to reap the benefit of it. She was the fourth mermaid his crew had caught, and whatever they did not drink they would sell. There was always a high price to be had for mermaid’s blood.

Instead, they had been caught.

The Pirate Supreme’s fleet flew flags of black, with a white mermaid emblazoned upon them. As soon as he’d seen the flags, Rake knew he was as good as dead. They all were.

Killing, robbing, and capturing of merchant ships and people were permitted by the Supreme. As long as the captains paid their tithes, of course. But mermaids. Mermaids were off-limits, lest the Sea rescind her kindness to all pirates. It was the law — the only law — not to capture mermaids. The Sea’s favor was the only thing that kept pirates safe from Imperials. The Imperials were stronger, after all. There were more of them, with more money, more boats, more men. But the Sea favored pirates, thanks to the Pirate Supreme, and their dedication to enforcing the one and only law.

And though Rake had only actually participated once — just to see, just to taste — he was just as guilty as everyone else aboard. He had not protested. He had seen things he had no right to see. Strange, terrible fish that glowed in the depths of the Sea. A shark that moved like an eel. And he had lost memories, though which ones he’d never know.

Rake felt the sting of seawater on his face, the wind whipping his hair about his ears. The gallows of the Pirate Supreme’s stronghold faced the Sea, at least. His last sight would be that of the sun rising over the Sea, casting golden, glinting light across the horizon that stretched endlessly before him.

A small mercy, which he surely did not deserve.

Already, half the crew had been summarily executed, their listless bodies dangling.

The rope about his neck itched, but he could not scratch, not with his hands bound. Useless hands on a useless body, put to a useless death after a useless life. At least he could see the Sea.

“You,” the Supreme called. “The ginger one.”

Rake nearly laughed. When was the last time he’d even seen himself in a looking glass? But still, he knew. His hair was red and ridiculous. The Pirate Supreme had addressed him.

“Yes, Your Majesty.”

“You don’t look afraid.”

“I’ve always been a fine actor,” Rake said. It was true that he did not fear Death, or the pain of Death at least, as much as he feared whatever punishment likely awaited him in the afterlife. Fear of any kind, he knew, was useless now. And more than anything, Rake hated uselessness.

The Pirate Supreme laughed, white teeth flashing.

“You amuse me. What is your name?”

“Rake.”

“I have an offer for you,” the Supreme said. Around them, people hummed and murmured. The Supreme’s presence at an execution was not the only unusual thing to happen that day. “Be an actor for me, red-haired Rake, for the rest of your days. And I’ll spare you on this one.”

Rake blinked. “You’d trust me?”

Again, the Supreme laughed, and their laughter was one with the sound of the waves that crashed beneath them. They were beautiful the way the Sea was beautiful — for both the Sea and the Supreme dealt in death. Power was beauty as embodied by them.

“Of course not. But you could spend your life proving your trustworthiness to me. And should your usefulness run out, I will see you right back to these gallows.”

Rake agreed to these terms. They cut his rope. Rake was not hanged that day. But he was cut with the tattoo of a mermaid upon the sensitive flesh of his ribs, so that he might remember his crimes and his promise.

Flora awoke to a face only a breath away from her own. The face belonged to a woman and bore the cracked remains of rouged cheeks and coal-black eyeliner. It was impossible to see what she looked like, her face was so close, but Flora felt sure she’d never seen her before.

The next thing Flora realized was that she was naked. That was strange all on its own, but was doubly so since Flora was never naked. It was very cold.

“Good,” the woman said. “You’re up.” But she did not move her face away.

“Yes.” There was a long pause, in which Flora hoped the meaning of what she saw would in any way become clear. It did not. “Think you could give me a little space?”

The woman blinked once, then did as Flora asked. She sat down, with some effort, on a small wooden chair in the corner of the room. “You were shot,” she said. “But I fixed you.”

Shot. Flora’s drowsiness evaporated. She put her hand to her shoulder reflexively but found nothing. Just a scar. The memories poured back into Flora, and with a start she remembered everything. She and Evelyn had fled the Dove. They had freed the mermaid. They had been pursued, and the mermaid had helped. But then Flora had been shot. And then, in flashes, the sting of sea-water, and she was on a beach? How had she lived? How long had she been asleep? Where was Evelyn?

Flora practically fell out of the bed in her haste to get moving. “Where is the Lady Hasegawa?” she demanded as she tried to jump back into her britches. It was a graceless affair, and she fell over more than once. But the old woman did not seem bothered in the least. “Evelyn?” she called, but no answer came. “EVELYN?”

“You’re welcome, by the way. It was a handy piece of work I did there. Your finger, too.”

And then, all at once, Flora was hit with a terrible notion.

The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea

The Mermaid, the Witch, and the Sea